It is time, in the opening days of the new year, to discuss in some depth the Chinese capture of a U.S. UUV off the coast of the Philippines. For those of you caught up in other matters, a good recap of the events can be found at Chris Cavas's

Defense News article*,

China Grabs Underwater Drone Operated by US Navy in South China Sea:

A Chinese Navy ship intercepted and grabbed a small, unmanned underwater vehicle

|

| U.S. Navy Photo |

(UUV) being operated by a US Navy survey ship on Thursday in waters west of the Philippines, US defense officials confirmed Friday.

It is not clear what — if anything — prompted the interception of an ocean glider, described by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) as “an autonomous, unmanned underwater vehicle used for ocean science.”

From the beginning, China has lied about the incident and then has engaged in a disinformation campaign to justify their acts, all the while subtly seeking to expand their power over the South China Sea.

Get the picture as set up by Pentagon spokesman:

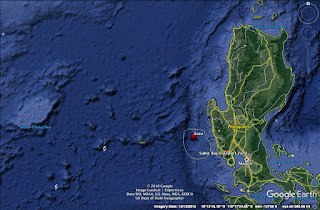

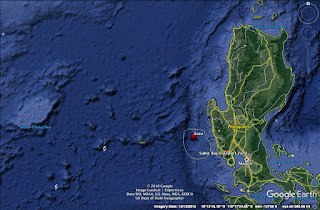

|

| Area of incident off Philippines |

Pentagon press secretary Peter Cook issued a statement Friday afternoon calling upon the Chinese government to immediately return the drone.

"Using appropriate government-to-government channels, the Department of Defense has called upon China to immediately return an unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV) that China unlawfully seized on Dec. 15 in the South China Sea while it was being recovered by a U.S. Navy oceanographic survey ship," Cook said in the statement.

"The USNS Bowditch (T-AGS 62) and the UUV -- an unclassified "ocean glider" system used around the world to gather military oceanographic data such as salinity, water temperature, and sound speed - were conducting routine operations in accordance with international law about 50 nautical miles northwest of Subic Bay, Philippines, when a Chinese Navy [People's Republic of China] DALANG III-Class ship (ASR-510) launched a small boat and retrieved the UUV.

"Bowditch made contact with the PRC Navy ship via bridge-to-bridge radio to request the return of the UUV," Cook continued. "The radio contact was acknowledged by the PRC Navy ship, but the request was ignored. The UUV is a sovereign immune vessel of the United States. We call upon China to return our UUV immediately, and to comply with all of its obligations under international law."

The Chinese ship was roughly 500 yards away from the Bowditch when the incident occurred, said Capt. Jeff Davis, Pentagon spokesman. Davis added that a crane was used to lift the unmanned system aboard the Chinese vessel.

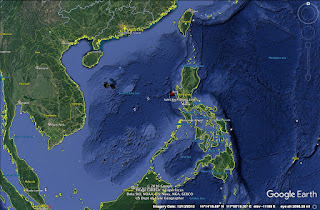

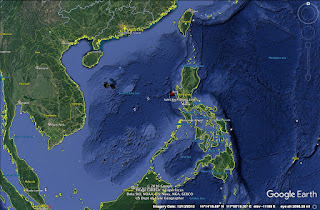

The defense official noted the location in the South China Sea was not in the proximity

|

| Area of incident in South China Sea |

of Scarborough Shoal, the site of a disputed Chinese island-building operation. “It’s not even close to Scarborough. It’s about 150 miles away,” the defense official said.

It's unclear what the Dalang 510 did after seizing the ocean glider. The Bowditch, the defense official said Friday, “remains in the area conducting normal operations.”

A few days after pirating the UUV, China returned the glider while lying about its actions, as set out in Sam LaGrone's USNI News piece

China Returns U.S. Navy Unmanned Glider:

Chinese officials claimed the glider was a hazard to navigation and they recovered the unmanned vehicle for the safety of the water. The U.S. took issue with Beijing’s interpretation of events.

Interpretation? It was a flat out lie.

Why would China grab a vessel clearly under control of a U.S. Naval vessel - and one that was also clearly in the process of being recovered by USNS Bowditch? Some interesting thoughts from a Japan Times opinion piece by Mark Valencia

U.S.-China drone spat: more than meets the eye:

Let’s be clear at the outset. The seizure of the UUV was certainly inappropriate and probably illegal — either as a simple theft or perhaps as a violation of the “sovereign immunity” of warships under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The U.S. military said the Bowditch — and the UUV — were carrying out scientific research in “international waters.” According to U.S. Navy spokesman Capt. Jeff Davis “the drone was seized while collecting unclassified scientific data.” The U.S. Defense Department said that “the incident was inconsistent with international law and standards of professionalism for conduct of navies at sea.”

***

China’s Defense Ministry explained that the Chinese Navy had taken an “unidentified object” (the UUV) out of the water “in order to prevent the device from causing harm to the safety of navigation and personnel of passing vessels.” Arguably this is a duty of mariners. China criticized U.S. hyping of the incident as a “theft.” China also argued that the activities of drones are a legal “gray area” in which the law is unclear. This is true. Relevant legal questions are whether the “sovereign immunity” clause extends to drones or any “equipment” launched from state vessels; does it apply to “non-ratifiers;” and did the Bowditch, by deploying the drones in the vicinity of another vessel, violate the duty to exercise “due regard” for the rights of other states, e.g. the duty not to present a hazard to navigation? After all the drone was not a “warship” as defined by UNCLOS because it was not “manned by a crew” and it is not a “vessel” because it is not used as a means of transportation.”

***

This analysis is not a justification of China’s action. But it offers possible explanations and background as to why it did what it did. At the least it gives a glimpse of the “cat and mouse” game going on between China and the U.S. in the South China Sea. Both sides are pushing — and even tearing — the legal envelope as they jockey for advantage. (note: "Mark J. Valencia is an adjunct senior scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies in Haikou, China)"

So, Mr. Valencia notes the power struggle while offering up China's weak justifications for its actions. The Chinese rationale was repeated by another scholar in Yan Yan's

The US Underwater Drone is not Entitled to Sovereign Immunity, which is set out below in its entirety:

On 20 December, 2016, the unmanned underwater vehicle (UUV) that had been seized by the Chinese Navy was handed back to the US Navy, bringing a conclusion to what US President-elect Donald Trump had labeled as an “unpresidented” event. The Chinese defense spokesman said that the UUV had been removed from the water to ensure the navigational safety of passing ships, but the US asserted that the UUV enjoyed sovereign immunity and that the Chinese action was in violation of international law. Jeff Davis, a Pentagon spokesman, described the UUV as a “sovereign immune vessel, clearly marked in English not to be removed from the water,” and said that it is US property and was lawfully conducting a military survey in the waters of the South China Sea. In a commentary written by James Kraska and Raul “Pete” Pedrozo, the authors hold the same argument that the UUV is a “vessel” that enjoys sovereign immune status, and as such the Chinese activity was a violation of international law.

The US argument is legally flawed if one takes a closer look at the rules of sovereign immunity in the law of the sea and how the US navy applies the UUV to its missions. Two types of ships are granted the sovereign immune status in the oceans according to articles 32, 95, and 96 of the 1982 UNCLOS: “warship” and “other government ships owned or operated by a State and used only on government non-commercial service.” First of all, I agree with Kraska and Pedrozo that the UUV is not a warship as defined by the 1982 UNCLOS. Article 29 of the UNCLOS defines “warship” as “a ship belonging to the armed forces of a State bearing the external marks distinguishing such ships of its nationality, under the command of an officer duly commissioned by the government of the State and whose name appears in the appropriate service list or its equivalent, and manned by a crew which is under regular armed forces discipline.” Although the Pentagon stated that the drone was US property, it was not “manned by crew,” and not clearly listed as a warship on active service.

But is the UUV a government “ship” owned or operated by a State and used only on government non-commercial service?

Kraska and Pedrozo hold that the UUV fits with the definition of “vessel” under Article 3 of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea as “every description of watercraft, including non-displacement craft, WIG craft, and seaplanes, used or capable of being used as a means of transportation on water.” But if one looks at the applications of the UUV by the US Navy, it is easy to see that it is not at all used “as a means of transportation on water,” but mostly for purposes of reconnaissance and submarine warfare.

The UUV is a subject that is able to operate underwater without a human occupant, and usually is divided into two categories: remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROVs) and autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs). For a long time in its history, application of the AUV was highly limited by the available technology. It was not until the last decade that, with more sophisticated processing capabilities and more efficient power supply systems, it could be used for an increased number of tasks.

The US Navy released the Unmanned Underwater Vehicles Master Plan in 2000 and updated it in 2004, describing the missions, capabilities, and technological and engineering issues of the UUV. The Master Plan is chartered by the Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy and the Submarine Warfare Division. The nine Sub-Pillar capabilities as identified and prioritized in the UUV Master Plan are: intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; mine countermeasures; anti-submarine warfare; inspection/identification; oceanography; communication/navigation network nodes; payload delivery; information operations; and time-critical strike. Among all, the top-priority mission is intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance. In addition to collecting data concerning the ocean surface (like electromagnetic and meteorological conditions) and underwater currents (like salinity and water temperature), the UUV is also capable of performing missions such as offshore surveillance, nuclear/biological detection, and satellite positioning. This is part of the reasons why global military powers have attached great importance to developing UUV-related technology. Highly adaptive to physical conditions and capable of performing multiple tasks in a highly efficient manner, the UUV has been widely viewed as a critical factor in future sea battles. In the wake of the Iraq War, the US began to see it as a primary threat to naval operations, and began to develop new types of UUV-based mine countermeasures.

Therefore, it’s very obvious to the author that the UUV is not used by the US Navy for the purpose of transportation and cannot be classified as a vessel that enjoys sovereign immune status. Rather, considering its functions and applications in the Navy, it is a lot more reasonable to classify it as a “machine,” “robot” or “military device,” which is not entitled to sovereign immunity.

In recent years, the rapid development of China’s Navy, particularly the development of its submarines, has drawn great attention from the US. By conducting intelligence gathering missions, the US has gradually built up an underwater surveillance and detection network covering China’s surrounding waters. It is reported that the US military has completed such networks in the Yellow Sea and East China Sea, and is now trying to build one in the South China Sea. It is predictable that more UUVs will be deployed by the US Navy in the South China Sea in the future. Although there are no definite rules on the application of such a “machine” or “device,” it is reasonable to assert that, like in any other international practice under the framework of the law of the sea, the operators of UUVs shall adhere to the spirit of peaceful use of the sea and ocean, show due regard to navigational safety, respect the coastal states’ laws and regulations, and refrain from using the UUV to perform such missions as undermining or threatening the coastal states’ security. Pointing fingers at each other is not conducive to the bilateral mil-mil relationship, or to the peace and stability in the South China Sea, as China and the US are now the two most important players in the region. (note:"Yan Yan is Deputy Director of the Research Center for Oceans Law and Policy at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou, China.")

Ms. Yan repeats the Chinese government misrepresentation of facts, ignores the proximity of the USNS Bowditch to the captured drone and then chooses to quibble about the definition of the term "vessel" as used by two distinguished maritime legal scholars, Kraska and Pedrozo. Their referenced piece is

China’s Capture of U.S. Underwater Drone Violates Law of the Sea:

“Vessels” are broadly defined in international maritime law, and are generally synonymous with “ships.” The London Dumping Convention defines a “vessel” as a “waterborne or airborne craft of any type whatsoever.” This expression includes in article 2(3) “air cushioned craft and floating craft, whether self-propelled or not.” Article 1(6) of the 1996 Protocol to the London Dumping Convention also includes “waterborne crafts and their parts and other fittings.” Similarly, article 3 of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea defines “vessel” as “every description of watercraft, including non-displacement craft, WIG craft, and seaplanes, used or capable of being used as a means of transportation on water.” This definition includes autonomous and even expendable marine instruments and devices, such as the U.S. drone stolen by the Chinese. The variation between manned systems and unmanned systems, such as size of the means of propulsion, type of platform, capability, endurance, human versus autonomous control and mission set, has not been a defining character of what constitutes a “vessel” or “ship.” Moreover, the seizure of the U.S. drone was a violation of COLREGS itself, which requires mariners to take affirmative steps to avoid closing on other vessels in the water.

Worth noting among the various treaties which define a "vessel" is the

International Convention On Salvage, 1989 which contains the following definition:

CHAPTER I

GENERAL PROVISIONS

Chapter I - General provisions

9

Article 1 - Definitions

10

For the purpose of this Convention:

11

(a) Salvage operation means any act or activity undertaken to assist a vessel or any other property in danger in navigable waters or in any other waters whatsoever.

12

(b) Vessel means any ship or craft, or any structure capable of navigation.

***

Article 4 - State-owned vessels

23

1. Without prejudice to article 5, this Convention shall not apply to warships or other non-commercial vessels owned or operated by a State and entitled, at the time of salvage operations, to sovereign immunity under generally recognized principles of international law unless that State decides otherwise.

24

2. Where a State Party decides to apply the Convention to its warships or other vessels described in paragraph 1, it shall notify the Secretary-General thereof specifying the terms and conditions of such application.

Let's look at the type of "glider" UUV-napped by the Chinese. As set out in

Slocum Glider,

The Slocum Glider is a uniquely mobile network component capable of moving to specific locations and depths and occupying controlled spatial and temporal grids. Driven in a sawtooth vertical profile by variable buoyancy, the glider moves both horizontally and vertically.

I would assert that being able to move to "specific locations" is a pretty clear indicator that a UUV of the Slocum glider type is capable of "navigation" and is, thereby, a "vessel" as defined by the Convention on Salvage.

Now, Ms. Yan argues that the key element of a "vessel" is that must be "used for transportation" - this assertion represents a rather lengthy legal history of of various court trying to distinguish "vessels" from other things that float but which are not capable of navigation unless towed by or otherwise moved by an outside force. A recent analysis is set out in

A Vessel Defined discussing the

Lozman case:

A majority of the justices on the US Supreme Court disagreed with the district court and Eleventh Circuit and held the floating home was not a vessel and could not be subject to a maritime lien. It focused its analysis on the meaning of the statutory phrase “capable of being used…as a means of transportation on water”. It declined to interpret the phrase broadly to encompass every item that can float. It reasoned some objects that float such as a wooden washtub, a plastic dishpan, a swimming platform on pontoons, a door taken off its hinges, or “Pinocchio when inside the whale,” are clearly not vessels. Rather, the court held a structure does not fall within the scope of the statutory definition of a vessel unless “a reasonable observer” looking at the structure’s physical characteristics and activities “would consider it designed to a practical degree for carrying people or things over water.”

To quote from the decision itself:

Not every floating structure is a “vessel.” To state the obvious, a wooden washtub, a plastic dishpan, a swimming platform on pontoons, a large fishing net, a door taken off its hinges, or Pinocchio (when inside the whale) are not “vessels,” even if they are “artificial contrivance[s]” capable of floating, moving under tow, and incidentally carrying even a fair-sized item or two when they do so. Rather, the statute applies to an “artificial contrivance . . . capable of being used . . . as a means of transportation on water.” 1 U. S. C. §3 (emphasis added). “[T]ransportation” involves the “conveyance (of things or persons) from one place to another.” 18 Oxford English Dictionary 424 (2d ed. 1989)(OED). Accord, N. Webster, An American Dictionary of the English Language 1406 (C. Goodrich & N. Porter eds. 1873) (“[t]he act of transporting, carrying, or conveying from one place to another”). And we must apply this definition in a “practical,” not a “theoretical,” way. Stewart, supra, at 496. Consequently, in our view a structure does not fall within the scope of this statutory phrase unless a reasonable observer, looking to the home’s physical characteristics and activities, would consider it designed to a practical degree for carrying people or things over water.

So "transportation" includes carrying "things" as well as people.

Again, the glider in question was undoubtedly transporting "things" including sensors and data relating to its navigation.

Ms. Yan's argument is legally insufficient.

Mostly what appears is a disinformation effort by the Chinese to forcefully claim more and more dominance in the South China Sea, even in areas clearly not within any arguable area of Chinese jurisdiction - thus the weak tea assertion of protecting "sea lanes" from a glider - a glider being closely monitored by the USNS ship and, in fact, in the process of being recovered by the US ship.

This aggressive assertion of hegemony over both waters in the high seas and in the EEZ of other countries (in this case the Republic of the Philippines) needs to be forcefully rejected and the Chinese lies about the circumstances of such incidents need to be vigorously countered.

UPDATE: Suggestions that China's own "glider" program is not up to the level of those of the West and a possible motive for why it was grabbed

here. Hat tip to

Ryan Martinson and to Scott Cheney-Peters.

UDPATE2: Interesting discussion at

Hybrid Warfare in the South China Sea: The United States’ ‘Little Grey (Un)Men':

There should be little doubt that the use of unmanned systems sets a strong political signal. Not only does it unambiguously establish the Washington and its allies’ willingness to counter Beijing’s “Little Blue Men,” it demonstrates the United States’ capacity to maintain its presence and reach into highly contested territory. Moreover, while providing additional intelligence to the United States and its allies, it signals an eagerness not only to challenge China’s posture but also to expand in another direction within the framework of hybrid/political warfare.

Perhaps a little overstated, since the UUV in question was not in what most would consider "highly contested territory" unless one grants China's claims to most of the South China Sea, claims already rejected by a tribunal as set out

here.

*All emphasis added by me